As we work on projects, it's important to document the features that we build, and to communicate them to users in a meaningful way.

After spending months manually communicating features for each release, we implemented an automated system that provides versioning within our application, using a tool called towncrier.

Towncrier

Towncrier is a utility that generates clear, user-friendly changelogs by managing "news fragments" - small files containing concise information about changes relevant to end users.

The core philosophy behind towncrier is: "Towncrier delivers the news which is convenient to those that hear it, not those that write it." This means focusing on what users need to know rather than technical implementation details.

Here's how it works in our implementation:

- We add a small (usually 1 line) file to each pull request, specifically formatted for towncrier. This is the user-facing summary for the pull request.

- Upon release, towncrier takes all such files, and compiles a summary of all changes.

- We display the summary within the application.

Example Towncrier File

A typical towncrier news fragment file in our implementation is simply a 1-line file with a sentence describing the change. Because our project uses JIRA, the filename uses the JIRA issue number (<JIRA-issue-number>.<type>.md). For example, for JIRA issue AB-123 the towncrier news fragment may be AB-123.feature.md or for JIRA issue AB-456 it could be AB-456.bugfix.md.

Allow equipment to have the same nameThis file is placed into a changes directory, and we make sure that each pull request has 1 new file in the changes directory (with a GitHub action we built).

Resulting CHANGES.md File

Upon release, a CHANGES.md file may look like:

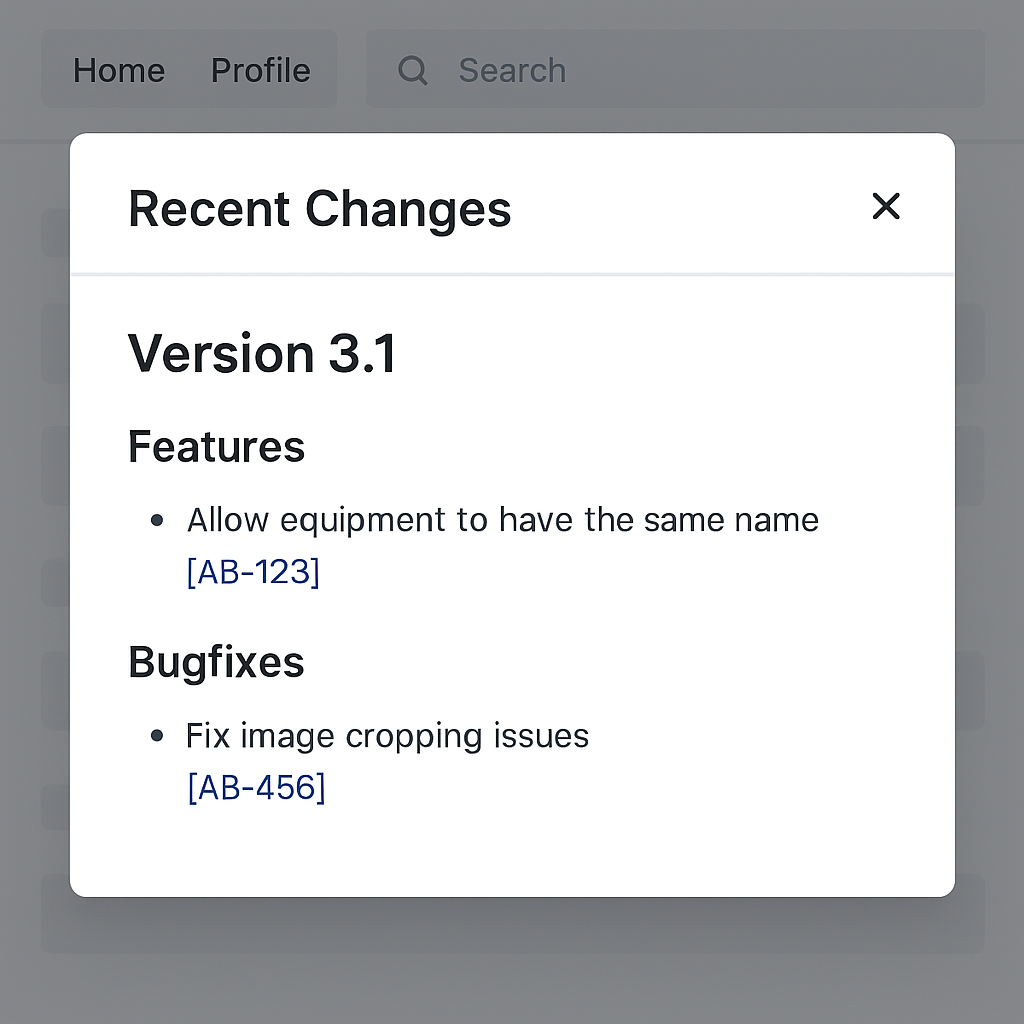

# Version 3.1

### Features

- Allow equipment to have the same name ([AB-123])

[AB-123]: https://our-company.atlassian.net/browse/AB-123

### Bugfixes

- Fix image cropping issues ([AB-456])

[AB-456]: https://our-company.atlassian.net/browse/AB-456Implementation

1. First, we added towncrier to our project requirement file and installed it.

2. Next, we decided that it would be helpful for each release to have "feature" and "bugfix" sections, so following the Towncrier tutorial, we added the following sections to our pyproject.toml file:

# Towncrier configuration

[tool.towncrier]

package = "our-application"

name = "Our Application"

directory = "changes" # The directory for all towncrier-specific files for a release

filename = "CHANGES.md" # The towncrier-created summary will go here

issue_format = "[{issue}]: https://our-company.atlassian.net/browse/{issue}"

[[tool.towncrier.type]]

directory = "feature"

name = "Features"

showcontent = true

[[tool.towncrier.type]]

directory = "bugfix"

name = "Bugfixes"

showcontent = true3. Next, we implemented a Python function to determine the next version number. There are a variety of ways to do this, and your approach will likely depend on your release process (whether it's manual or automatic, and whether the next version should be based on a user input or be decided automatically). For us, it was a user input to a GitHub Action, and we named our Python function next_version().

4. We already had a GitHub Action for manual deploys, and we added the following sections to it:

- name: Install dependencies

run: |

python -m pip install -e .

python -m pip install towncrier

- name: Get next version number

run: |

echo "version=$(python -m next_version ${{ inputs.bump }})" >> "$GITHUB_ENV"

- name: Store release notes

run: |

towncrier build --draft --version $version | tail -n +3 > /tmp/changes.txt

- name: Build full changelog

run: |

towncrier build --yes --version $version

- name: Commit changelog

run: |

git config user.name "our-github-action"

git config user.email "our-github-action@our-company.com"

git commit -am "Update CHANGES for $version"

git tag "v$version" --file=/tmp/changes.txt --cleanup=whitespace

git push --follow-tagsAs a result, running the release updates our CHANGES.md file with all of the changes since the last release.

5. The last step was to make this file visible in our application. We created a view which simply returned the formatted CHANGES.md file, and made it visible to users. From there, a number of upgrades can be added, such as highlighting key changes, detecting the last version seen by a particular user, and showing the most recent changes in a modal.

The CHANGES.md file referenced above could appear to users in a modal like:

Results

This solution worked great for our users, because it allowed them an easy way to see the application's changes or to search for a particular change.

Moreover, it greatly simplified our process of communicating changes from a manual action to something automated. Finally, it created a dedicated place for viewing application changes, removing the need to search emails or messages.

Limitations

While the process has worked great, it relies on developers to be strategic about pull requests and the descriptions they use for each one. A team that is not committed to writing meaningful summaries for each pull request could reduce the usefulness of the process. Also, forgetting to include the towncrier-specific file in each pull request could result in undocumented features or bugfixes, though it is also possible to configure continuous development pipelines to assert that each pull request has a towncrier file.

Conclusion

Overall, implementing towncrier was a beneficial change that simplified our release communication from a manual process into an automated system that provides users with clear, accessible information about the changes in each release.